Faithfulness and Patriotism

Mark 6:1-13

Lyndale UCC- July 7, 2024

Rev. Dr. Rebecca Voelkel

Gathered here in the mystery of this hour, gathered here in One Strong Body, gathered here in the struggle and the power, Spirit draw near.

For the sermon time this morning, I am going to share some context and a few brief reflections and then I’m going to invite us into a few minutes of conversation together around the theme of faithfulness and patriotism.

In our scripture reading for today, Jesus has just been travelling around the region where he has been performing exorcisms and healings. And now he has returned to his hometown synagogue where he stands up and starts teaching. But, instead of excitement about the hometown boy who has done them proud, Jesus’ hearers are more like, “who does this upstart think he is? He thinks he can tell us what to do? Give me a break!”

The text tells us: Then Jesus said to them, “Prophets are not without honor, except in their hometown and among their own kin and in their own house.” And he could do no deed of power there, except that he laid his hands on a few sick people and cured them.

Jesus’ message falls on barren ground and closed ears. It is from that place that Jesus then moves to call the disciples.

This is the first point I would lift up in our conversation this morning: faithfulness, prophetic ministry, being invited into following Jesus is not the same as success.

OK, so back to the passage: Jesus’ message has fallen on barren ground and closed ears. From this place, he calls the disciples. Our text says:

Then he went about among the villages teaching. He called the twelve and began to send them out two by two and gave them authority over the unclean spirits… So they went out and proclaimed that all should repent. They cast out many demons and anointed with oil many who were sick and cured them.

Every time I read about Jesus’ ministry of exorcism, I have a visceral reaction. I think, particularly as a lesbian, the specter of too many of my queer elders, and frankly, queer contemporaries, experiencing literal exorcisms as well as attempted psychiatric ones makes me deeply suspicious of that word. And today is no different. But, as I’ve shared before, I have been greatly helped by Ched Myers’ commentary on Mark’s gospel called Binding the Strong Man.

Myers encourages us to recognize a lot of symbolism in Mark’s gospel. In particular, Myers says about Mark’s gospel, “From the moment he strides into a Capernaum synagogue, it becomes clear that Jesus’ Kingdom project is incompatible with the local public authorities and the social order they represent. A ‘demon’ immediately demands that Jesus justify his attack upon the authority of the [political and religious] establishment; Jesus vanquishes this challenge and commences his ministry of healing.”

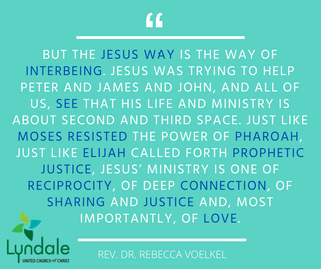

In other words, in order to be about the constructive ministry of genuine healing, love, justice, and peace, Jesus must also be about the deconstructive ministry of exorcizing the status quo of some people having most of the power and stuff, and others being outcast, impoverished, and oppressed.

And this is the second piece I’d like for us to consider: Jesus’ call to the disciples, and to any of us who would be followers, or, as the word “disciple” means, students of Jesus, we are invited into the interconnected work of deconstructing the status quo of some having most of the power and stuff and others being outcast, impoverished, and oppressed AND healing and building a world where love, peace, and justice are alive and well.

- Faithfulness is not the same as success by the world’s standards

- Discipleship is about deconstructing things that harm many and benefit a few AND discipleship is about healing and building a world of love, peace and justice.

We just got back from Ireland and Scotland. We were in Inverness, Scotland the night of the presidential debate and we were in Hacketstown, Ireland last Tuesday night having dinner with Maggie’s cousins, all of whom are practicing Catholics and one of whom spent twenty years as the chief architect of retiring Ireland’s national debt. As we sat at dinner, they asked really, really good questions about the rise of white nationalism here in the US and, in particular, Project 2025. And they also reflected on authoritarian Victor Orban in Hungary, the recent European Union parliamentary elections where far-right representatives from both Germany and France were just elected, and today’s election in France, where far-right, fascist candidates look to be poised to win. And they asked us what we, as Christians, are going to do?

[pause]

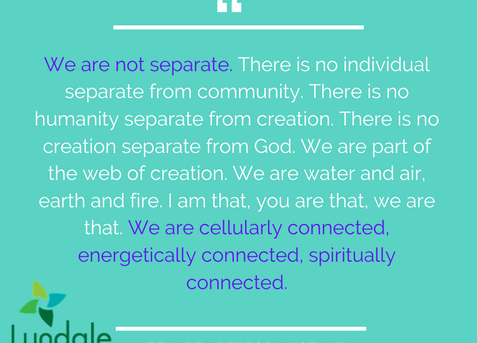

One other thing from our scripture passage that always touches me is that Jesus doesn’t send the disciples out alone, they go with a partner into ministry. And almost all of Jesus’ ministry is done in the context of community.

I don’t honestly know how to fully answer Maggie’s cousins’ questions. But I do know that part of the answer is that we are given to each other in beloved, deep community, here at Lyndale and in thousands and thousands of other spiritual communities of people seeking to be students of the Way of love, justice, and peace.

So, on this Fourth of July weekend, amidst the global rise of white nationalism and threats to our democracy, what does your faith lead you to do and be? What does the relationship between faithfulness and patriotism look like for you?

I’d love to invite you to turn to one or two neighbors and share your responses and thoughts about these questions. We’ll take about ten minutes to talk to each other. And then, I’d love to hear a few of your reflections.

[sharing]

I return thanks to God for this community and for being students together of the Way of love, peace, and justice. Amen.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed